|

ROBERT E. KLEIN

Robert 'Rob' E. Klein is an American artist who is perhaps best known for his work with Disney's characters especially Donald Duck and Gyro Gearloose. He has written and drawn numerous stories for a number of Europe's leading Disney publishers.

My Memories of Carl Barks

I approached the door of the suburban house, not knowing what to expect. I stood at his front door, deciding whether or not I was ready to ring the bell. I wanted to make a good impression. My heart almost burst out through my chest when footsteps approached. What was I doing there - a shy, introverted, young man, who had been invited to an almost complete stranger’s house? That stranger just happened to be Carl Barks.

I had hundreds of questions to ask my hero about his life, likes and dislikes, details of his stories, his work methods, etc. After all, his exciting worldwide adventures of Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, that I loved so much, would later inspire me towards both my careers. I wanted to know everything about him. But, I didn’t want to come off as a “drooling fan”, or a magazine reporter, and thus, scare him away. I wondered how he and his wife would react to me. He had seemed pleasant enough and easy going on the telephone. But, often, people act differently in person.

But what events led me to his door? Like for many others, Carl Barks had a large influence on my life. From the age when I learned to read, I read his 1940s stories in my older cousins’ comic books, which were eventually left to me. When reading the stories of the Ducks’ foreign adventures, I longed to visit those faraway places. I sat for hours with my father, pointing out on the globe and atlases, where Donald and Uncle Scrooge had been. From those experiences, I chose a career as an environmental planner and economist for United Nations’ development projects in Africa, the Middle East, and the Far East. Of course, as a youngster, I didn’t know that artist’s name – only that his story writing and artwork stood out from the rest. I thought of him as “The Good Artist”.

As a teenager, my love for Barks’ work made me want to have every page of it that I could get my hands on, in a permanent format. I decided to photocopy of all the pages of his stories, and have them bound professionally in a set of fancy volumes. In 1966, I discovered “The Collectors Book Store” in Hollywood, California. It was owned by Malcolm Willits. He informed me that “The Good Artist” was named Carl Barks. I frequented his shop often, talking about comics. Some months later, when Willits was in the process of auctioning off some of Barks’ original drawings for him, I told him about my project. He let me get Barks’ unpublished drawings photographed.

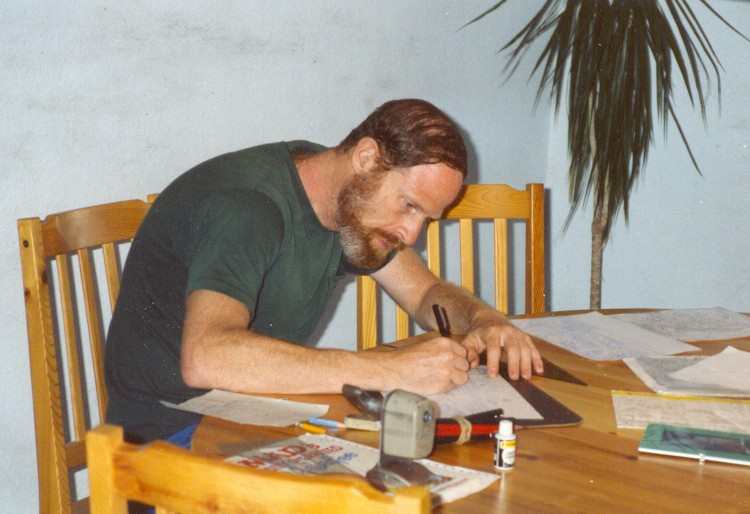

Malcolm thought that my ambitious undertaking, - hand coloring of the black and white photocopied pages, and making street maps of Duckburg, would be interesting to Mr. Barks. So, he called Carl on the telephone, and had me talk to him. I was flabbergasted. Only finding out the name of “The Good Artist” a few months before, I was now talking directly to him. He seemed very polite and good-natured on the telephone, and genuinely interested in my project. Carl and I exchanged telephone numbers (Malcolm hadn’t given me Carl’s), as well as addresses. We wrote some letters and talked a few more times over the next three years. Near the very end of the 1960s, when I informed him that my Works of Carl Barks volumes were complete, and I already had two volumes colored, he invited me to visit him at his home in Goleta, California. I guessed that the main reason he invited me was to see what kind of weirdo would dedicate so much time and effort to worshipping stories about fictional characters. Nevertheless, I was in seventh heaven. I was going to meet my hero in person!

The door finally opened, and all my fears disappeared when a tall, gray haired man with a jolly looking smile opened the door. His wife Garé was just behind. They welcomed me into their cozy home, and ushered me to a seat on their sofa. The first thing I noticed was several nice paintings of wildlife and forest and pastoral scenes. Carl told me, proudly, that Garé had painted the professional-looking animal scenes. He then modestly informed me that he had painted some of those pastoral landscapes. When I mentioned that I like Garé’s paintings very much, Garé gave me three packages of greeting cards with prints of her paintings on the covers. I still have them all, to this day.

The couple gave me a tour of their house, which included the studio where Carl worked. It was very orderly, with his drawing table, a bookshelf with his National Geographic Magazines and a few other things, another small shelf with the original comic books with his stories, which he used for reference, and his painting easel, which was then empty. When I visited again in 1973, it had one of his Disney Duck paintings on it, in progress. Donald and his nephews were sailing on a small sailboat, inspired by his original cover drawing for Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories No. 108.

After Carl asked to see my volumes of his work, The Barkses accompanied me out to my car, and helped me bring the books inside. As we carried them into the house, I fully expected Carl to say he was glad I hadn’t had the books with me at the doorstep, or they would have thought I was an encyclopaedia salesman. Soon, Carl was flipping through the volumes. He was especially curious about the Duckburg, Duck County and Calisota maps and Duck Family Tree, which I had placed at the beginning of Volume I.

Garé mentioned that taking some photos would be nice. When I told them I hadn’t brought a camera, and had never even owned one, they looked at each other, and their eyes said: “What kind of fan is this?” I wonder if they thought that like some primitive tribesman, I believed taking a photo of me would steal my soul? Regardless of my peculiarity, Garé got her camera, and took a few pictures of Carl and me, standing behind my books, and standing together, without them. Carl and Garé kept those photos for themselves. No doubt he wanted a picture of a set of books made to honor his work. But, I suppose, he and Garé also wanted to remember what a Duck worshipper looked like. I never got prints of the photos, probably because I didn’t ask for them, and I told them I didn’t keep photographs. Carl did try to put me at my ease by telling me that when he heard that one of his fans drew maps of his Duck’s city and state, he’d expected to see a small, wormy character wearing a plaid vest and square spectacles standing at his door. I felt better when he said, “You look normal enough to me.” I’m glad he didn’t have a psychologist on hand.

Once again, Carl and I sat on their sofa, discussing his work. I knew that I had only a limited time, so I had to limit my questions to the things that were most important to me. I learned that he was a very humble man, who, at that time, had no idea of the effects he had on his young readers’ lives. In fact, he admitted that before some fans had told him to the contrary, he didn’t know if very many kids read Disney comics, as he had NEVER seen any child buy one. He mentioned that when he lived in San Jacinto, California in the early 1950s, he used to stand inside the local drugstore, to see who bought which comic books. He said the kids read all sorts of “superhero” comics, but he never even saw one pick up a Disney comic book. It is a very strange coincidence, that I used to visit my grandparents in summers in the early 1950s in San Jacinto. It turns out that they lived only a few blocks away from the Barkses. In fact, I used to visit the same drugstore on Main Street, that Carl frequented for his “spying” on comic book readers. I always bought all the Disney comic books that came out while I was visiting there, so I wouldn’t miss those issues.

Apparently, our paths never crossed, or he would have seen a child buying comic books with his stories. A chance meeting wouldn’t have affected me back then, not knowing who he was. As a child, I thought some man named Walt Disney drew the comics. As an adolescent, I thought a talented artist at the Walt Disney Studios created them. Barks was discovered around that time by a few local San Jacinto children who besieged his home for some weeks. Luckily, Disney’s secret didn’t leak out to the rest of the world. Had he introduced himself to me as the prolific Disney Duck artist, I would have told everybody I knew all over The World (I have a big family). The Barkses would have had to change their name and move to Bora Bora.

I told Carl that I thought his drawing and story writing were far and above the level of the other Disney Comic book artists. He thanked me, but seemed uneager to bask in the glory of the pedestal on which his fans place him. He said nothing about his artwork, but did comment on his writing. He said he always tried to do the best job he could in making a story. He wouldn’t feel right turning in a story that he wouldn’t like reading, himself. Furthermore, he stated that he kept plugging away those long hours, to make sure his bosses liked his work, so he could keep his “cushy job”. He told me that he enjoyed being a free-lance cartoonist working at home a lot more than any office job or hard labor, as most of his other jobs had been. Nevertheless, I was shocked to hear that he feared he might be fired or laid off. I had thought his status as the best artist/writer at Western Publishing was recognized by his employers, and they’d be afraid to lose him. I guess that as a solitary type, Barks relished working alone, without a boss looking over his shoulder so much, that he was willing to put up with his long hours for relatively low pay.

Barks was amazed that adults, even highly educated professionals, would take his work so seriously. He mentioned that he had met a few of his fans who, amazingly, seemed to know what was in every panel of every story he wrote. But, he was still surprised that an adolescent would go beyond memorizing his stories, taking the additional time to research them thoroughly, and draw detailed maps of fictional geography of funny animal characters’ environs. He was also surprised that maps could even be drawn, as he said he had never taken into consideration where he had previously placed individual landforms, buildings, streets, parks, etc. in earlier stories, when working on a current story. In actuality, the sheer number of his Duck story pages made it possible for me to draw a realistic map of a middle sized city of about 300,000 people, as he portrayed Duckburg to be. He stated that he only used a character or geographical place as it was needed for the story he was currently working on. Neither did he have an overall plan of the geography or history of Duckburg or Calisota, nor the Duck family tree. If he needed Duckburg to have a seacoast, it would have one. If it needed to be surrounded by forests or farmland, it wouldn’t be on the coast. If a story needed a blizzard, Duckburg would be in snow country. But, in summer, Duckburg also had palm trees. Carl said that Duckburg was a place where “anything could happen”. But, he admitted that he didn’t like when things happened just as if by magic. He said he always wanted the occurrences in his stories to seem at least possible, if not considered too deeply. I told him that was one of the main reasons why his stories were the best.

Carl also mentioned that he never intended to put deeper meanings, philosophical or moral statements into his stories, the way some of his fans assumed that he did. He said he just tried to write simple, straight forward stories that he, himself, would enjoy reading. He said that the extended Duck family just grew out of the need for new plot elements to wrap around Donald, and that also, unbeknownst by him, the geography of Duckburg and Calisota was crystallizing with almost every story.

In talking about the missing, unpublished story pages, Barks was apologetic about not remembering very many of the details, but reminded me that those were panels he’d drawn roughly fifteen to twenty years before, and he’d not seen them since. So, I was happy to learn what little I could. About the 1945 Christmas story opening half page, he said: “The story was rejected by my editor because Jones was being too rough with Donald around Christmas time. Those scenes didn’t go along with the Christmas spirit Disney was trying to convey at that time.” He remembered that Donald was sitting by the fireplace in his comfy chair, reading old fashioned tomes about Christmas in olden times. Donald had a look of discovery in his eyes and was saying something like: “Great Stuff! Great Stuff!” He was coming to the idea that people nowadays have forgotten the “true meaning of Christmas”. In 1985, after a lot of practice trying to mimic Barks’ drawing style, I used what he described as the basis for creating a new half page for that story.

We also talked about “The Golden Apple Story”, which Malcolm had already told me had been rejected by Barks’ editors. He said that it was not only never printed, but the original art was lost. It had been planned for Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories No. 144, in 1952. Carl told me that the story was about Daisy’s jealousy over Donald’s falling for a beautiful Queen of Duckburg’s Apple Festival. He said that his editor (Chase Craig) thought that Daisy’s “fit of anger” against Donald, in which she threw “everything at him but the kitchen sink”, was too “unladylike”. He also told me that there was a traditional race through the woods, in which Duckburg’s men chased after the Apple Queen (as in the Greek myth of Atalanta). She had a basket of golden apples. “Every time she threw down an apple, Donald would grab for it, and when he looked up, she was gone, as if she vanished into thin air. Every time she ran behind a tree, Donald would follow, but she would disappear.” It can be assumed that the winner of the race, in catching the Apple Queen, would gain the honor of being “Apple King”, and also win the right to be her date for the Apple Festival’s concluding dance, which could be appropriately named, “The Apple Pickers’ Ball”. He added a few different details each time I asked him about it. But he apologized for not remembering much of the plot. However, he did tell me several more details than were printed in his published interviews. Knowing that, a few years ago, I wrote and storyboarded a new story, based on all he told me, and logical assumptions based on Barks’ typical storytelling methods. Unfortunately, it hasn’t been bought by a Disney publisher, to this point.

We sat on the couch talking for several hours, only interrupted by Garé serving lunch for the three of us. The sandwiches were very good. I really appreciate how hospitable the Barkses were to me during my two visits.

When I told Carl that I thought his work stood out way beyond the other writers and artists, he didn’t blush. I think he had an inkling that he was putting in more time and effort to make his stories than most of the other artists. I said that I was really disappointed that only three of his stories appeared in Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories in 1950. He agreed with me that the stories by those other artists were poorly written. He said “Those were written by people who didn’t know how to write stories. They went about it the wrong way. They just thought about Donald’s typical day, and what things might come across his path. He would wake up, get dressed, and walk out his front door. Then, the author would think of a character that Donald could meet or bump into, or an incident that might occur, that he would get involved in. That kind of story is a disjointed sequence of events that usually doesn’t make sense. And, it’s boring, too!”

I asked Carl how he went about choosing his supporting characters. He told me that because generally he first decided what story he wanted to tell, the need for specific characters came directly from what was needed to carry out the plot’s action. He mentioned that Uncle Scrooge, Gladstone Gander, Gyro Gearloose, Duckburg’s mayor, and even the Junior Woodchucks, were created just for the needs of a single story he was working on. But he did add that the Junior Woodchucks, politicians and lazy people were “easy to poke fun at”. It was clear that he believed in a good day’s work for a day’s pay, and that each person should pull his own weight. That was also clear from his dedication to his work, by putting in long hours to make sure his stories were as good as they could be. I got the impression that he had little love for the idle rich, lazy ne’er-do-wells, snobs, blowhard politicians, braggarts, arbitrary bureaucrats, cruel bosses and the like.

When I told Barks about my visits to my grandparents’ house in San Jacinto when he lived there, and that our paths might have crossed way back then, he had a good chuckle about the “fates” and what a small world this is. I told him about my memories of the large turkey ranch on Soboba Road, and how those thousands of turkeys gobbling and pecking made a lasting impression on me. I asked him if seeing them had been his inspiration for his many stories with aggressive and dangerous turkeys (Donald’s turkey hunting stories, turkeys biting off Hairy Harry’s beard). Carl answered that he hadn’t considered that, but that it was certainly possible. He remembered the incredible sound of the gobbling, and the intense smell of the place, and the sound of their flapping wings. “Those turkeys can be ornery birds!” he added.

After my 1973 visit, I wrote only once after hearing that the Barkses were being hounded by too many fans wanting to visit him, interview him, and get him to draw autographed pictures. I could imagine that their privacy was being eroded. So, I chose to end contact with them, not wanting to contribute to their burden.

But, a full eighteen years later, in 1991, after working full time in comic book production for a few years, and after my drawing and story writing had improved significantly, I contacted Carl once again. I sent him photocopies of several Duck stories I wrote in storyboard form. He wrote back that he had wondered what happened to “The young redheaded fan who made bound volumes of my work and maps of Duckburg”. He said that he enjoyed my stories, and was impressed that I had returned to school to learn to draw at the age of forty. He was happy to hear that I was now doing work I really enjoy. It seems apparent that he hadn’t remembered my name, offhand, after all those years, until I wrote him again. But he certainly had some remembrance our meetings and memory of what I looked like. That is why I believe he represented me in his 1976 oil painting “Parade in Duckburg”, as the red headed bear policeman holding the crowd back. After all, ....... when have you seen a redheaded bear?

I’ll always cherish the legacy Carl Barks left me. During the years he was writing his comic book stories, he always had a notepad and pencil on his night table, by his bed, so he could write down ideas he came up with during the night. He said he still had a list of a few hundred unused funny character names. I'm honored that he “gave” me “Flameflicker Lampwick” to use in my stories, as I wish. I haven’t been able to use it yet. And, it will probably take me at least ten more years to invent a character that can live up to that name. But I’m determined to do it.

|

This contribution is published for the first time in its full length by special permission of the author © 2007 All rights reserved.

| http://www.cbarks.dk/themeetingsklein.htm | Date 2008-06-23 |