| . .

.

.

.

.

.

WDCS131

'The Unlucky Golfer'

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

FC0178

Christmas on Bear Mountain

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

FC0029

The Mummy's Ring

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

WDCS182

'The Raging Bull'

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

WDCS198

'Hero of the Ball'

|

|

I was never able to just sit

down and write a longhand script. First, I jotted

down a bunch of gags that would come to my mind.

Then I would start hooking the gags together, and

pretty soon I'd have a sort of a little synopsis.

From that, I'd break it down into a longer

synopsis. Make a mark every two or three lines

and think, 'Well, that will make one page', and 'This'll

make another page'. By the time I'd get to the

bottom of my synopsis, I'd know whether I was

going to have enough material.

Any time that I wrote a script,

when I got through with it, I'd lay it aside,

pick it up the next morning, and read it. If it

didn't read with a lot of rhythm going right on

through, I'd work on it another day or so until I

got to where it sounded good, then start drawing.

With the drawing, too, I would pick up sheets

that I had done two or three days before and look

at them. If the business didn't look right, I

didn't mind doing it over. I was after a certain

quality.

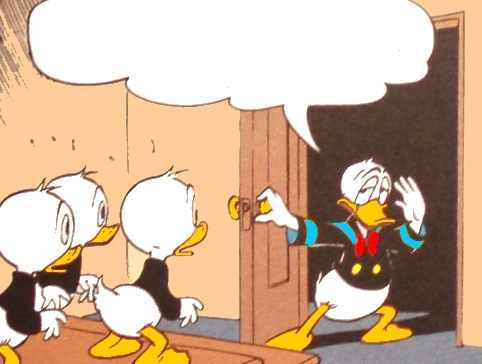

I was letting the story build up

to a certain point in which the reader would be

expecting the conventional end, and then I would

fool the reader by dragging in something that was

completely ridiculous, making it look plausible.

Example: Donald's unexpected 'retirement' to the

privacy of his closet after a turmoilish day in WDCS131

'The Unlucky Golfer'.

The choice of words also was one of

Barks' passions: I'll rather use one word

instead of four, he once stated, and

consequently he polished and re-polished his

material to perfection. I tried to make it as

brief as possible. If I could find a word that

would express what four words say, I would use

that one word. So I had a sort of short, very

crisp dialogue in my stories as a result of that

contracting them down. And, in order to get the

dialogue as short as possible, sometimes it was

necessary to even count the syllables, and I

would do that if it got down to it, and that also

helped to create an even flow, so that it was

almost like prose poetry the way the ducks voices

would come in.

I tried to end each page,

especially toward the latter part of the story,

with a little zinger that would carry the reader

forward. Sometimes the story would not lend

itself to that kind of presentation, but that's

the way we learned it at the Disney Studios

working on the short subjects. There had to be a

little climax just about every few seconds on the

screen, so that's the way I tried to write the

duck stories.

I bought a large bulletin board,

and when I'd get a half sheet or a comic page

done in pencil, I'd stick it up there, and then

the next one, and the next one, and after I got

about five of them done, I would sit back and

look at the display and read the continuity.

Sometimes I would take down two or three sheets

and do a lot of erasing and changing. I was able

to visualize my story progress much better that

way.

Later, I finally got so polished at writing those

stories that I didn't need to work by that method.

I could just do a half page and stick it up on

the shelf. I was able to visualize it more or

less from my longhand, rather than having to have

it up there in pencil drawings. But I think that

my best work was done back in those years, when I

had, say, five pages all laid out in blue pencil

to criticize.

On inventing new characters:

There were definite reasons for it. When I

had used Donald and his three nephews several

times in a row, for example, I'd always think one

ought to do something else, make up new gags, and

at some point the idea came to me that one could

also introduce new characters for this purpose. I

introduced Gladstone Gander, for example,

originally as a foil for Donald, a rival, who in

his first story (WDCS088 'Cocky

Combattants' - Editor's remark) concerning

a bet, was just as dumb as Donald. He only later

developed into such a lucky duck.

As for Scrooge McDuck, he just appeared as a

grumpy uncle and had something to do with Donald,

because the story required it (FC0178

Christmas on Bear Mountain - Editor's

remark). But the more I used him, the more

strongly I realized that one can't always draw a

character in a bad light, any more than one can

show the same character as having exclusively

good qualities. That just gets boring.

Scrooge was created more by chance, in contrast

to Magica de Spell, about whom I had more of an

idea that here was a new, regular figure to be

used. Magica was introduced much more

intentionally, as a wicked witch who was always

after Scrooge's first-earned dime (U$36

The Midas Touch - Editor's remark).

I thought at the time: Disney's always had

witches who were ugly and repulsive, so why

shouldn't I draw one that's not ugly, but

outright sexy? That's why she is Italian...

You've got to be darn sure that

your idea is presented. If it's going to take

three or four drawings to present that idea, the

timing of it comes in on how much development you

do in the first panel, how much you do in the

second, how much in the third, and if you keep

the development just enough that the reader can

figure out what is coming, and then in the fourth

panel, give it to him with a big sock right in

the face. That's what I consider timing.

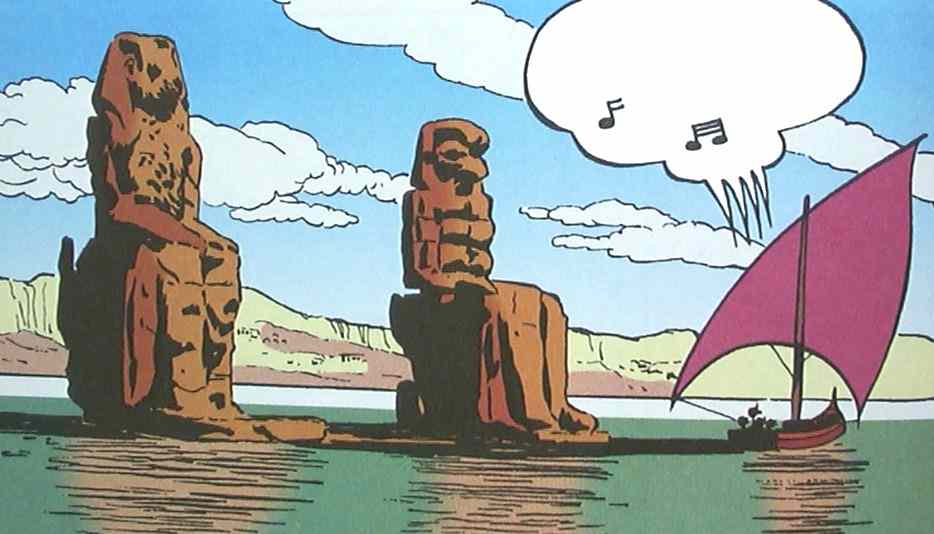

I don't know exactly why I did

so much research for my stories, but I had the

feeling the ducks had to go to real places.

Otherwise the stories would look silly. I know in

the other duck stories in the comics they went to

islands like Booga Booga or something like that,

places that didn't have any relation to reality.

And they made their drawings in little squiggly

backgrounds that didn't have the right character,

for example the South Seas.

When I sent the ducks to an island in the South

Seas, I gave it a name that sounded very much

like it could actually be on the map. And I would

go and look at pictures of plants there, and

islands and mountains, and all the rest, and I

made my background look like the ducks went to

just such a place (Barks primarily used

National Geographic and Encyclopedia Britannica

as his sources - Editor's remark). Example: The

Ducks pass by the Colossal of Memnon on the Nile

in FC0029 The Mummy's Ring.

Ideas generally come in a very

complicated form, and you've got to strip them

down to make them useable. Boil a gag down to its

simplest form and it is readily discernible to

anybody who sees it.

Don't try to use too many ideas

in a story plot. You have to be selective. Be

mean. Throw perfectly lovely gags in the waste

basket.

My stories are timeless. They

can be read again and again and are still good

years later. I always tried for that, just as I

always tried to keep the stories as international

as possible. That's why I, as far as I could,

avoided particular American things like baseball,

because I hardly think that you, in Germany,

would understand a baseball story.

I always tried to write a story

in such a manner that I wouldn't mind buying it

myself. I know that I was expected to write for

an audience of 12-year olds. But my faith in the

12-year old's intelligence was greater than the

publisher's. In my opinion the kids should have

relevant experience for their 10-cent.

When struggling for a story, I

would often ask myself: what locale do I want to

draw? Do I want to draw a forest, the sea with

sailboats, or would it be down in the mines and

caves? As soon as I thought of a locale, I could

come up with a reason for putting characters in

that locale.

I took a piece of paper and drew

a few funny situations on it, just ideas that I

had. What should I have the ducks do today? When

I had enough individual gags, I'd make a short

summary and develop the entire story, as a whole.

That was one difference between me and the other

artists and writers. I took individual gags,

tightened them up and built the highpoint of the

story out of them, and then I went back - how

could the ducks get into such a situation, or

more concretely: Why did the bull smash the china,

how did he get there (plot idea from WDCS182

'The Raging Bull' - Editor's remark)?

I always proceeded very logically, and the

individual logical steps were made as funny as

possible.

Once in a while the little kids

would get themselves in some pretty bad messes

and then Donald would have a chance to rescue

them. But mostly it was Donald who got clobbered

and the kids who rescued him. It worked out

better, and it appealed to more people that way,

because the readers were kids themselves. They

liked to feel a little bit superior to the uncle

who was strutting around.

In fact I laid it right on the

line. There was no difference between my

characters and the life my readers were going to

have to face. When the Ducks went out in the

desert, so did Joe Blow down the street with his

kids. When Donald got buffeted around, I tried to

put it over in such a way that kids would see it

could happen to them. Unlike the superhero comics,

my comics had parallels in human experience.

I often liked to put the ducks

into situations where they could be at sea. There

is something romantic about harbors and sunken

ships that appeals to all kids.

There have been times when I

felt nervous about taking a chance with a plot,

but it wasn't enough to stop me. I'd compromise a

bit if I felt I was getting too wild. I've

approached every subject with my teeth chattering

and knees knocking. Getting new ideas was the big

nerve-racker. Often I'd feel I'd pumped the well

dry and hadn't another idea in my system - I'd

get real scared. I can remember times when I got

so scared that when I did come up with an idea, I

almost cried with relief at having gotten over

that hump again.

Of all the 500 stories I wrote,

there was about 10 of them that started with

suggestions from someone else. Example:

Barks' daughter Peggy suggested the plot for WDCS198

'Hero of the Ball'.

I was letting the story build up

to a certain point in which the reader would be

expecting the conventional end, and then I would

fool the reader by dragging in something that was

completely ridiculous, making it look plausible.

Writing was a mental strain.

Once I had gotten the general idea, then that was

a moment of joy ... It wasn't genius or even

unusual talent that made the stories good, it was

patience and a large waste basket.

|