Carl Barks always meticulously kept

records of the salaries he earned from his different employers

during his adult life. In this page you are primarily presented

to his incomes from two of his greatest sources: The Calgary

EyeOpener (1932-1935) and The Walt Disney Corporation (1935-1942).

The page shows how diverse - and to some extent uncertain - his

income was during these 11 years, and often he had to add to it

by selling gags and cartoons to other publishers and media.

The contents of Barks' early payment sheets have never been

published before, but this is now done, because they can add

interesting information - sometimes with direct bearing on

certain incidents and transactions - relating to events already

known by his fans. In order not to fill the page with tiresome

columns of figures or both exact and more general figures

depending on the importance of the individual salaries, it has

been decided to present the material as a whole in a more easily

readable fashion with explanatory commentaries on a year-by-year

basis.

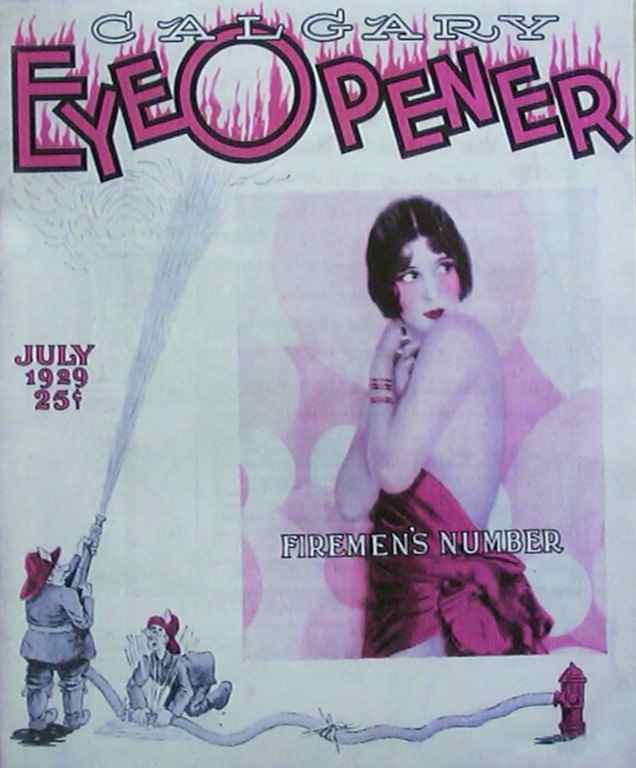

CALGARY EYEOPENER

|

1932 Barks started his work for the Calgary

EyeOpener (CEO) as a free-lancer in 1928, and he

contributed to the magazine on a regular basis. But in

1932 he took the plunge and moved from California to the

publishing office in Minnesota to become a full-time

employee. He was paid 55 dollars regularly every two

weeks starting in January, and he ended up with 65

dollars at the end of the year. From time to time (during

his entire stay at CEO) Barks cashed in a few dollars on

cartoons for long-gone magazines. Among the most unusual

receivers was EN-AR-CO, a small company in the oil

refining business, to which he several times supplied

gags and ideas, as they also dabbled in various puzzle

games(!). You can see a small example of their

advertising from the time HERE. |

1933 Although CEO was a fulfilling workplace for

Barks it became increasingly harder for the publisher to

make ends meet, which also affected the salary policy for

the employees. Payments became more and more erratic; for

example, one month he received 25 dollars one day and 20

dollars the next, whereupon he had to wait several weeks

for the next payment. At the end of the year Barks could

register total salary dues of 269 dollars! To put this

amount in perspective his annual rent amounted to 384

dollars. |

|

1934 The erratic salary policy continued, and

Barks' salary lacked behind constantly. Furthermore, his

biweekly salary dropped to 56 dollars, probably causing

him to continue 'moonlighting' for other small magazines.

Barks' annual rent was now down to 312 dollars suggesting

that he had chosen to move premises due to the uncertain

tendencies at CEO. |

|

1935 From the beginning of the year Barks got a

raise to 61 dollars every two weeks, but already in July

it returned to 56 dollars. When Barks saw an

advertisement from Disney looking for new artists he

openly considered the possibility. He was then offered -

and given - a salary of 80 dollars, but felt that he had

to leave CEO, which was grossly mismanaged at the time.

Barks received his last paycheck (of 80 dollars) on

October 25, and moved back to California. |

THE WALT DISNEY CORPORATION

|

1935 Barks was fully aware that he had to take a

considerable cut in his hitherto wages by joining Disney,

and he started out on November 4 by receiving 20 dollars

biweekly! After all, he was a new man at the job, and he

was first attached to an art course on the premises. |

1936 During the year Barks' salary grew to 22.40,

to 27.37 only to end at 34.84 dollars, and the

explanation for these rapid raises was that he made

himself positively noticed for his serious work in

several areas; he contributed several gag ideas for Snow

White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) which got him 5

dollars or more per idea (see more HERE), he worked overtime, and, above all, he

was transferred from tedious in-betweening in the

animation department to the story section, which was

better paid. This job was a direct result of an idea for Modern

Inventions (1937), which brought him a personal

check from Walt Disney himself for 49.77 dollars. |

|

1937 The fact that Barks' work was appreciated is

mirrored in his steadily growing salaries; already from

February he received a whopping 63.76 dollars every two

weeks only to end the year at 74.32 dollars! Some of the

explanation was, of course, that he from now on

functioned as a part-time Story Director on Disney's

cartoon shorts. |

|

1938 Barks' salary followed an ascending curve in

those years; he ended the year at 88.20 dollars. This was

also the last year he contributed gags and cartoons to

CEO and other magazines. Instead he frequently got paid

bonuses for gag ideas to Disney's multiple projects. In

fact, his bonuses totalled 1,254.35 dollars and

individual gag ideas equalled 122.50 dollars. One of

Barks' many 'projects' was supplying gag ideas for the

daily Donald Duck newspaper strip at 2.44 to 9.80 dollars

per idea (see more HERE). |

|

1939 Apart from a few more newspaper strip gags

Barks contented himself with his normal income, which was

by then more or less fixed at 88.20 dollars. Instead he

used all his free hours in an attempt to become a full

time newspaper cartoon artist (see more HERE),

which logically resulted in a decrease in his income. |

|

1940 Again, Barks contributed a few gags and

cartoons to other magazines, and he took up his old money-maker

of supplying Disney with gag ideas. Also, he sold Disney

stocks for 200 dollars. |

|

1941 For some unknown reason the meticulous Barks

left his income sheet unfinished after three months, but

until then he earned 1,251.00 dollars, which equals 104.25

dollars biweekly. Two isolated entries seem somewhat

puzzling; in February he received a special bonus of 175

dollars for Timber (1941), and in May he got 259

dollars for Early to Bed (1941). The bonuses are

especially interesting, because Barks was not Story

Director on any of these shorts, and it is not known how

he earned them. |

|

1942 This was the year when Barks decided to break away from his highly profitable job at Disney with the intention of becoming a successful chicken farmer! But before the secure income cord was cut he made two comic book stories with other artists. In May Barks received 100 dollars for Pluto Saves the Ship (1942) and 320 dollars for Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold! (1942). At the time he was a free-lancer for Western Publishing (see more HERE), an employer he would work for until his official retirement in 1966. The chicken farm was quickly abandoned - luckily for us... |

Below

are two randomly chosen examples of Barks' payment

receipts from Disney. |

This

website has many pages focusing on Barks' work for both

companies. |

| http://www.cbarks.dk/THEEARLYPAYMENTS.htm | Date 2008-11-13 |